Sexy Tab

History of the United States

"American history" redirects here. For the history of the continents, see History of the Americas.

| Part of a series on the |

| History of the United States |

|---|

|

| Timeline |

By ethnicity[show]

|

By topic[show]

|

The history of the United States as covered in American schools and universities typically begins with either Christopher Columbus's 1492 voyage to the Americas or with the prehistory of theNative peoples; the latter approach has become increasingly common in recent decades.[1]

Indigenous peoples lived in what is now the United States for thousands of years and developed complex cultures before European colonists began to arrive, mostly from England, after 1600. The Spanish had early settlements in Florida and the Southwest, and the French along the Mississippi River and Gulf Coast. By the 1770s, thirteen British colonies contained two and a half million people along the Atlantic coast, east of the Appalachian Mountains. After driving the French out of North America in 1763, the British imposed a series of new taxes while rejecting the American argument that taxes required representation in Parliament. Tax resistance, especially the Boston Tea Party of 1774, led to punishment by Parliament designed to end self-government in Massachusetts. All 13 colonies united in a Congress that led to armed conflict in April 1775. On July 4, 1776, the Congress adopted the Declaration of Independence drafted by Thomas Jefferson, proclaimed that all men are created equal, and founded a new nation, the United States of America.

With large-scale military and financial support from France and military leadership by GeneralGeorge Washington, the American Patriots won the Revolutionary War. The peace treaty of 1783 gave the new nation most of the land east of the Mississippi River (except Florida). The national government established by the Articles of Confederation proved ineffectual at providing stability to the new nation, as it had no authority to collect taxes and had no executive. A convention called inPhiladelphia in 1787 to revise the Articles of Confederation instead resulted in the writing of a new Constitution, which was adopted in 1789. In 1791 a Bill of Rights was added to guarantee rights that justified the Revolution. With George Washington as the nation's first president and Alexander Hamilton his chief political and financial adviser, a strong national government was created. When Thomas Jefferson became president he purchased the Louisiana Territory from France, doubling the size of American territorial holdings. A second and last war with Britain was fought in 1812.

Driven by the doctrine of Manifest Destiny, the nation expanded beyond the Louisiana purchase, all the way to California and Oregon. The expansion was driven by a quest for inexpensive land for yeoman farmers and slave owners. This expansion was controversial and fueled the unresolved differences between the North and South over the institution of slavery in new territories. Slavery was abolished in all states north of the Mason–Dixon line by 1804, but the South continued to profit off the institution, producing high value cotton exports to feed increasing high demand in Europe. The 1860 presidential election of anti-slavery Republican Abraham Lincoln triggered the secession of seven (later eleven) slave states to found the Confederacy in 1861. The American Civil War (1861-1865) ensued, with the overwhelming material and manpower advantages of the North decisive in a long war, as Britain and France remained neutral. The result was restoration of the Union, the impoverishment of the South, and the abolition of slavery. In the Reconstruction era (1863–77) legal and voting rights were extended to the Freedmen (freed slaves). The national government emerged much stronger, and because of theFourteenth Amendment, it gained the explicit duty to protect individual rights. However, legal segregation and Jim Crow laws left blacks as second class citizens in the South with little power until the 1960s.

The United States became the world's leading industrial power at the turn of the 20th century due to an outburst of entrepreneurship in the North and Midwest, and the arrival of millions of immigrant workers and farmers from Europe. The national railroad network was completed with the work of Chinese immigrants, and large-scale mining and factories industrialized the Northeast and Midwest. Mass dissatisfaction with corruption, inefficiency and traditional politics stimulated the Progressive movement, from the 1890s to 1920s, which led to many social and political reforms. In 1920 the 19th Amendment to the Constitution guaranteed women's suffrage (right to vote). This followed the 16th and 17th amendments in 1909 and 1912, which established the first national income tax and direct election of U.S. senators to Congress.

Initially neutral in World War I, the U.S. declared war on Germany in 1917, and funded the Allied victory the following year. After a prosperous decade in the 1920s, the Wall Street Crash of 1929 marked the onset of the decade-long world-wide Great Depression. Democrat Franklin D. Roosevelt ended the Republican dominance of the White House and implemented his New Deal programs for relief, recovery, and reform. They defined modern American liberalism. These included relief for the unemployed, support for farmers, Social Security and a minimum wage. After the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, the United States enteredWorld War II alongside the Allies especially Britain and the Soviet Union. It financed the Allied war effort and helped defeat Nazi Germany in Europe and, with the detonation of newly invented atomic bombs, Japan in the Far East.

The United States and the Soviet Union emerged as rival superpowers after World War II. Around 1947 they began the Cold War, confronting one another indirectly in the arms race and Space Race. U.S. foreign policy during the Cold War was built around the support of Western Europe and Japan, and the policy of "containment" or stopping the spread of Communism. The U.S. became involved in wars in Korea and Vietnam to stop the spread. In the 1960s, especially due to the strength of the civil rights movement, another wave of social reforms were enacted during the administrations of Kennedy and Johnson, enforcing the constitutional rights of voting and freedom of movement to African Americans and other minorities. Native American activism also rose. The Cold War ended when the Soviet Union dissolved in 1991, leaving the United States the world's only superpower. As the 21st century began, international conflict centered around the Middle East and spread to Asia and Africa following the September 11 attacks by Al-Qaeda on the United States. In 2008 the United States had its worst economic crisis since the Great Depression, which has been followed by

Contents

[hide]- 1 Prehistory

- 2 Pre-Columbian era

- 3 Colonial period

- 4 18th century

- 5 American Revolution

- 6 Early years of the republic

- 7 19th century

- 8 20th century

- 9 21st century

- 10 See also

- 11 References

- 12 Textbooks

- 13 Further reading

- 14 External links

Prehistory[edit]

Main article: Prehistory of the United States

Pre-Columbian era[edit]

Main article: Pre-Columbian era

See also: Native Americans in the United States

It is not definitively known how or when the Native Americans first settled the Americas and the present-day United States. The prevailing theory proposes that people migrated from Eurasia across Beringia, a land bridge that connected Siberia to present-dayAlaska during the Ice Age, and then spread southward throughout the Americas and possibly going as far south as the Antarcticpeninsula. This migration may have begun as early as 30,000 years ago[2] and continued through to about 10,000+ years ago, when the land bridge became submerged by the rising sea level caused by the ending of the last glacial period.[3] These early inhabitants, calledPaleoamericans, soon diversified into many hundreds of culturally distinct nations and tribes.

The pre-Columbian era incorporates all period subdivisions in the history and prehistory of the Americas before the appearance of significant European influences on the American continents, spanning the time of the original settlement in the Upper Paleolithic period to European colonization during the Early Modern period. While technically referring to the era before Christopher Columbus' voyages of 1492 to 1504, in practice the term usually includes the history of American indigenous cultures until they were conquered or significantly influenced by Europeans, even if this happened decades or even centuries after Columbus' initial landing.

Colonial period[edit]

Main article: Colonial history of the United States

After a period of exploration sponsored by major European nations, the first successful English settlement was established in 1607.[4] Europeans brought horses, cattle, and hogs to the Americas and, in turn, took back to Europe maize, turkeys, potatoes, tobacco, beans, and squash. Many explorers and early settlers died after being exposed to new diseases in the Americas. The effects of new Eurasian diseases carried by the colonists, especially smallpox and measles, was much worse for the Native Americans, as they had no immunityto them. They suffered epidemics and died in very large numbers, usually before large-scale European settlement began. Their societies were disrupted and hollowed out by the scale of deaths.[5][6]

Spanish, Dutch, and French colonization[edit]

Main articles: Spanish colonization of the Americas, Dutch colonization of the Americas, and French colonization of the Americas

Spanish explorers were the first Europeans with Christopher Columbus' second expedition, which reached Puerto Rico on November 19, 1493; others reached Florida in 1513.[7] Quickly Spanish expeditions reached the Appalachian Mountains, the Mississippi River, theGrand Canyon[8] and the Great Plains. In 1540, Hernando de Soto undertook an extensive exploration of Southeast. Also in 1540Francisco Vásquez de Coronado explored from Arizona to central Kansas.[9] The Spanish sent some settlers, mostly to New Mexico. Small Spanish settlements that eventually grew to become important cities include San Antonio, Texas, Albuquerque, New Mexico,Tucson, Arizona, Los Angeles, California, and San Francisco, California. [10]

New Netherland was the 17th-century Dutch colony centered on present-day New York City and the Hudson River Valley, where they traded furs with the Native Americans to the north and were a barrier to Yankee expansion from New England. The Dutch were Calvinists who built the Reformed Church in America, but they were tolerant of other religions and cultures. The colony was taken over by Britain in 1664. It left an enduring legacy on American cultural and political life, including a secular broadmindedness and mercantile pragmatism in the city, and a rural traditionalism in the countryside typified by the story of Rip Van Winkle. Notable Americans of Dutch descent include Martin Van Buren, Theodore Roosevelt,Franklin D. Roosevelt, Eleanor Roosevelt and the Frelinghuysens.[11]

New France was the area colonized by France from 1534 to 1763. There were few permanent settlers outside Quebec and Acadia, but the French had far-reaching trading relationships with Native Americans throughout the Great Lakes and Midwest. French villages along theMississippi and Illinois rivers were based in farming communities that served as a granary for Gulf Coast settlements. The French settled New Orleans, Mobile and Biloxi, and established plantations in Louisiana.

The Wabanaki Confederacy became military allies of New France through the four French and Indian Wars, while the British colonies were allied with the Iroquois Confederacy. During the French and Indian War, the North American front of the Seven Years War, New England fought successfully against French Acadia. The British removed Acadians from Acadia (Nova Scotia) and replaced them with New England Planters.[12] Eventually, some Acadians resettled in Louisiana, where they developed a distinctive rural Cajun culture that still exists. They became American citizens in 1803 with the Louisiana Purchase.[13] Other French villages along the Mississippi and Illinois rivers were absorbed when the Americans started arriving after 1770, or settlers moved west to escape them.[14] French influence and language in New Orleans, Louisiana and the Gulf Coast was more enduring; New Orleans was notable for its large population of free people of color before the Civil War.

British colonization[edit]

Further information: British colonization of the Americas

The strip of land along the eastern seacoast was settled primarily by English colonists in the 17th century, along with much smaller numbers of Dutch and Swedes. Colonial America was defined by a severe labor shortage that employed forms of unfree labor such as slavery andindentured servitude, and by a British policy of benign neglect (salutary neglect) that permitted the development of an American spirit distinct from that of its European founders.[16] Over half of all European immigrants to Colonial America arrived as indentured servants.[17]

The first successful English colony was established in 1607, on the James River atJamestown Virginia, which began the American Frontier. It languished for decades until a new wave of settlers arrived in the late 17th century and established commercial agriculture based on tobacco. Between the late 1610s and the Revolution, the British shipped an estimated 50,000 convicts to their American colonies.[18] A severe instance of conflict was the 1622 Powhatan uprising in Virginia, in which Native Americans killed hundreds of English settlers. The largest conflict between Native Americans and English settlers in the 17th century was King Philip's War in New England;[19] The Yamasee War in South Carolina was as bloody.[20]

The massacre of Jamestown settlers in 1622. Soon the colonists in the South feared all natives as enemies.

New England was initially settled primarily by Puritans who established the Massachusetts Bay Colony in 1630, although there was a small earlier settlement in 1620 by a similar group, the Pilgrims, at Plymouth Colony. The Middle Colonies, consisting of the present-day states of New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and Delaware, were characterized by a large degree of diversity. The first attempted English settlement south of Virginia was the Province of Carolina, with Georgia Colony the last of the Thirteen Colonies established in 1733.[21]

The colonies were characterized by religious diversity, with many Congregationalists in New England, German and Dutch Reformed in the Middle Colonies, Catholics in Maryland, andScots-Irish Presbyterians on the frontier. Sephardic Jews were among early settlers in cities of New England and the South. Many immigrants arrived as religious refugees: French Huguenots settled in New York, Virginia and the Carolinas. Many royal officials and merchants were Anglicans.[22]

Religiosity expanded greatly after the First Great Awakening, a religious revival in the 1740s led by preachers such as Jonathan Edwards. American Evangelicals affected by the Awakening added a new emphasis on divine outpourings of the Holy Spirit and conversions that implanted within new believers an intense love for God. Revivals encapsulated those hallmarks and carried the newly created evangelicalism into the early republic, setting the stage for the Second Great Awakening beginning in the late 1790s.[23] In the early stages, evangelicals in the South such as Methodists and Baptists preached for religious freedom and abolition of slavery; they converted many slaves and recognized some as preachers.

Each of the 13 American colonies had a slightly different governmental structure. Typically a colony was ruled by a governor appointed from London who controlled the executive administration and relied upon a locally elected legislature to vote taxes and make laws. By the 18th century, the American colonies were growing very rapidly because of ample supplies of land and food, and low death rates. They were richer than most parts of Britain, and attracted a steady flow of immigrants, especially teenagers who came as indentured servants. The tobacco and rice plantations imported African slaves for labor from the British colonies in the West Indies, and by the 1770s they comprised a fifth of the American population. The question of independence from Britain did not arise as long as the colonies needed British military support against the French and Spanish powers; those threats were gone by 1765. London regarded the American colonies as existing for the benefit of the mother country, a policy known as mercantilism.[24]

18th century[edit]

Political integration and autonomy[edit]

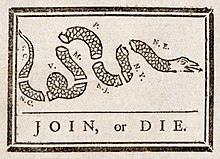

Join, or Die: This 1756 political cartoon by Benjamin Franklin urged the colonies to join together during the French and Indian War.

The French and Indian War (1754–1763) was a watershed event in the political development of the colonies. It was also part of the larger Seven Years' War. The influence of the main rivals of the British Crown in the colonies and Canada, the French and North American Indians, was significantly reduced which U.S territory expanded into New France that was between the Thirteen Colonies and Louisiana. Moreover, the war effort resulted in greater political integration of the colonies, as reflected in the Albany Congress and symbolized byBenjamin Franklin's call for the colonies to "Join or Die". Franklin was a man of many inventions-one of which was the concept of a United States of America, which emerged after 1765 and was realized in July 1776.[25]

Following Britain's acquisition of French territory in North America, King George III issued theRoyal Proclamation of 1763 with the goal of organizing the new North American empire and protecting the native Indians from colonial expansion into western lands beyond the Appalachian Mountains. In ensuing years, strains developed in the relations between the colonists and the Crown. The British Parliament passed the Stamp Act of 1765, imposing a tax on the colonies without going through the colonial legislatures. The issue was drawn: did Parliament have this right to tax Americans who were not represented in it? Crying "No taxation without representation", the colonists refused to pay the taxes as tensions escalated in the late 1760s and early 1770s.[26]

1846 painting of the 1773 Boston Tea Party.

The Boston Tea Party in 1773 was a direct action by activists in the town of Boston to protest against the new tax on tea. Parliament quickly responded the next year with theCoercive Acts, stripping Massachusetts of its historic right of self-government and putting it under army rule, which sparked outrage and resistance in all thirteen colonies. Patriot leaders from all 13 colonies convened the First Continental Congress to coordinate their resistance to the Coercive Acts. The Congress called for a boycott of British trade, published a list of rights and grievances, and petitioned the king for redress of those grievances.[27] The appeal to the Crown had no effect, and so the Second Continental Congress was convened in 1775 to organize the defense of the colonies against the British Army.

Ordinary folk became insurgents against the British even though they were unfamiliar with the ideological rationales being offered. They held very strongly a sense of ”rights” that they felt the British were deliberately violating – rights that stressed local autonomy, fair dealing, and government by consent. They were highly sensitive to the issue of tyranny, which they saw manifested in the arrival in Boston of the British Army to punish the Bostonians. This heightened their sense of violated rights, leading to rage and demands for revenge. They had faith that God was on their side.[28]

The American Revolutionary War began at Concord and Lexington in April 1775 when the British tried to seize ammunition supplies and arrest the Patriot leaders.

Population density in the American Colonies in 1775.

American Revolution[edit]

Main articles: American Revolution and History of the United States (1776–1789)

Washington's surprise crossing of the Delaware River in Dec. 1776 was a major comeback after the loss of New York City; his army defeated the British in two battles and recaptured New Jersey.

The Thirteen Colonies began a rebellion against British rule in 1775 and proclaimed their independence in 1776 as the United States of America. In theAmerican Revolutionary War (1775–1783) the American capture of the British invasion army at Saratoga in 1777 secured the Northeast and encouraged the French to make a military alliance with the United States. France brought in Spain and the Netherlands, thus balancing the military and naval forces on each side as Britain had no allies.[29]

General George Washington (1732–1799) proved an excellent organizer and administrator, who worked successfully with Congress and the state governors, selecting and mentoring his senior officers, supporting and training his troops, and maintaining an idealistic Republican Army. His biggest challenge was logistics, since neither Congress nor the states had the funding to provide adequately for the equipment, munitions, clothing, paychecks, or even the food supply of the soldiers.

As a battlefield tactician Washington was often outmaneuvered by his British counterparts. As a strategist, however, he had a better idea of how to win the war than they did. The British sent four invasion armies. Washington's strategy forced the first army out of Boston in 1776, and was responsible for the surrender of the second and third armies at Saratoga (1777) and Yorktown (1781). He limited the British control to New York City and a few places while keeping Patriot control of the great majority of the population.[30]

The Loyalists, whom the British counted upon too heavily, comprised about 20% of the population but never were well organized. As the war ended, Washington watched proudly as the final British army quietly sailed out of New York City in November 1783, taking the Loyalist leadership with them. Washington astonished the world when, instead of seizing power for himself, he retired quietly to his farm in Virginia.[30] Political scientist Seymour Martin Lipset observes, "The United States was the first major colony successfully to revolt against colonial rule. In this sense, it was the first 'new nation'."[31]

On July 4, 1776, the Second Continental Congress, meeting in Philadelphia, declared the independence of "the United States of America" in the Declaration of Independence. July 4 is celebrated as the nation's birthday. The new nation was founded on Enlightenment ideals of liberalism in what Thomas Jefferson called the unalienable rights to "life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness", and dedicated strongly to republican principles. Republicanism emphasized the people are sovereign (not hereditary kings), demanded civic duty, feared corruption, and rejected any aristocracy.[32]

Early years of the republic[edit]

Main article: History of the United States (1789–1849)

See also: First Party System and Second Party System

Confederation and Constitution[edit]

Further information: Articles of Confederation and History of the United States Constitution

In the 1780s the national government was able to settle the issue of the western territories, which were ceded by the states to Congress and became territories; with the migration of settlers to the Northwest, soon they became states. Nationalists worried that the new nation was too fragile to withstand an international war, or even internal revolts such as the Shays' Rebellion of 1786 in Massachusetts. Nationalists—most of them war veterans—organized in every state and convinced Congress to call the Philadelphia Convention in 1787. The delegates from every state wrote a new Constitution that created a much more powerful and efficient central government, one with a strong president, and powers of taxation. The new government reflected the prevailing republican ideals of guarantees of individual libertyand of constraining the power of government through a system of separation of powers.[33]

The Congress was given authority to ban the international slave trade after 20 years (which it did in 1807). A compromise gave the South Congressional apportionment out of proportion to its free population by allowing it to include three-fifths of the number of slaves in each state's total population. This provision increased the political power of southern representatives in Congress, especially as slavery was extended into the Deep South through removal of Native Americans and transportation of slaves by an extensive domestic trade.

To assuage the Anti-Federalists who feared a too-powerful national government, the nation adopted the United States Bill of Rights in 1791. Comprising the first ten amendments of the Constitution, it guaranteed individual liberties such as freedom of speech and religious practice, jury trials, and stated that citizens and states had reserved rights (which were not specified).[34]

The New Chief Executive[edit]

George Washington — a renowned hero of the American Revolutionary War, commander-in-chief of the Continental Army, and president of the Constitutional Convention—became the first President of the United States under the new Constitution in 1789. The national capital moved from New York to Philadelphia and finally settled in Washington DC in 1800.

The major accomplishments of the Washington Administration were creating a strong national government that was recognized without question by all Americans.[35] His government, following the vigorous leadership of Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton, assumed the debts of the states (the debt holders received federal bonds), created the Bank of the United States to stabilize the financial system, and set up a uniform system of tariffs (taxes on imports) and other taxes to pay off the debt and provide a financial infrastructure. To support his programs Hamilton created a new political party—the first in the world based on voters—the Federalist Party.

Thomas Jefferson and James Madison formed an opposition Republican Party (usually called the Democratic-Republican Party by political scientists). Hamilton and Washington presented the country in 1794 with the Jay Treaty that reestablished good relations with Britain. The Jeffersonians vehemently protested, and the voters aligned behind one party or the other, thus setting up the First Party System. Federalists promoted business, financial and commercial interests and wanted more trade with Britain. Republicans accused the Federalists of plans to establish a monarchy, turn the rich into a ruling class, and making the United States a pawn of the British.[36] The treaty passed, but politics became intensely heated.[37]

The Whiskey Rebellion in 1794, when western settlers protested against a federal tax on liquor, was the first serious test of the federal government. Washington called out the state militia and personally led an army, as the insurgents melted away and the power of the national government was firmly established.[38]

Washington refused to serve more than two terms—setting a precedent—and in his famous farewell address, he extolled the benefits of federal government and importance of ethics and morality while warning against foreign alliances and the formation of political parties.[39]

John Adams, a Federalist, defeated Jefferson in the 1796 election. War loomed with France and the Federalists used the opportunity to try to silence the Republicans with the Alien and Sedition Acts, build up a large army with Hamilton at the head, and prepare for a French invasion. However, the Federalists became divided after Adams sent a successful peace mission to France that ended theQuasi-War of 1798.[36][40]

Slavery[edit]

Main article: Slavery in the United States

During the first two decades after the Revolutionary War, there were dramatic changes in the status of slavery among the states and an increase in the number of freed blacks. Inspired by revolutionary ideals of the equality of men and their lesser economic reliance on it, northern states abolished slavery, although some had gradual emancipation schemes. States of the Upper South made manumission easier, resulting in an increase in the proportion of free blacks in the Upper South from less than one percent in 1792 to more than 10 percent by 1810. By that date, a total of 13.5 percent of all blacks in the United States were free.[41] After that date, with the demand for slaves on the rise with the development of the Deep South for cotton cultivation, the rate of manumissions declined sharply, and an internal slave trade became an important source of wealth for many planters and traders.

19th century[edit]

Jeffersonian Republican Era[edit]

Territorial expansion; Louisiana Purchase in white.

Thomas Jefferson defeated Adams for the presidency in the 1800 election. Jefferson's major achievement as president was the Louisiana Purchase in 1803, which provided U.S. settlers with vast potential for expansion west of the Mississippi River.[42]

Jefferson, a scientist himself, supported expeditions to explore and map the new domain, most notably the Lewis and Clark Expedition.[43] Jefferson believed deeply in republicanism and argued it should be based on the independent yeoman farmer and planter; he distrusted cities, factories and banks. He also distrusted the federal government and judges, and tried to weaken the judiciary. However he met his match in John Marshall, a Federalist from Virginia. Although the Constitution specified a Supreme Court, its functions were vague until Marshall, the Chief Justice (1801–35), defined them, especially the power to overturn acts of Congress or states that violated the Constitution, first enunciated in 1803 in Marbury v. Madison.[44]

War of 1812[edit]

Main article: War of 1812

Americans were increasingly angry at the British violation of American ships' neutral rights in order to hurt France, the impressment (seizure) of 10,000 American sailors needed by the Royal Navy to fight Napoleon, and British support for hostile Indians attacking American settlers in the Midwest. They may also have desired to annex all or part of British North America.[45][46][47][48][49] Despite strong opposition from the Northeast, especially from Federalists who did not want to disrupt trade with Britain, Congress declared war in June 18, 1812.[50]

The war was frustrating for both sides. Both sides tried to invade the other and were repulsed. The American high command remained incompetent until the last year. The American militia proved ineffective because the soldiers were reluctant to leave home and efforts to invade Canada repeatedly failed. The British blockade ruined American commerce, bankrupted the Treasury, and further angered New Englanders, who smuggled supplies to Britain. The Americans under General William Henry Harrison finally gained naval control of Lake Erie and defeated the Indians under Tecumseh in Canada,[51] while Andrew Jackson ended the Indian threat in the Southeast. The Indian threat to expansion into the Midwest was permanently ended. The British invaded and occupied much of Maine.

The British raided and burned Washington, but were repelled at Baltimore in 1814—where the "Star Spangled Banner" was written to celebrate the American success. In upstate New York a major British invasion of New York State was turned back. Finally in early 1815 Andrew Jackson decisively defeated a major British invasion at the Battle of New Orleans, making him the most famous war hero.[52]

With Napoleon (apparently) gone, the causes of the war had evaporated and both sides agreed to a peace that left the prewar boundaries intact. Americans claimed victory in February 18, 1815 as news came almost simultaneously of Jackson's victory of New Orleans and the peace treaty that left the prewar boundaries in place. Americans swelled with pride at success in the "second war of independence"; the naysayers of the antiwar Federalist Party were put to shame and it never recovered. The Indians were the big losers; they never gained the independent nationhood Britain had promised and no longer posed a serious threat as settlers poured into the Midwest.[52]

Era of Good Feelings[edit]

Main article: Era of Good Feelings

As strong opponents of the war, the Federalists held the Hartford Convention in 1814 that hinted at disunion. National euphoria after the victory at New Orleans ruined the prestige of the Federalists and they no longer played a significant role.[53] President Madison and most Republicans realized they were foolish to let the Bank of the United States close down, for its absence greatly hindered the financing of the war. So they chartered the Second Bank of the United States in 1816.[54][55]

The Republicans also imposed tariffs designed to protect the infant industries that had been created when Britain was blockading the U.S. With the collapse of the Federalists as a party, the adoption of many Federalist principles by the Republicans, and the systematic policy of President James Monroe in his two terms (1817–25) to downplay partisanship, the nation entered an Era of Good Feelings, with far less partisanship than before (or after), and closed out the First Party System.[54][55]

The Monroe Doctrine, expressed in 1823, proclaimed the United States' opinion that European powers should no longer colonize or interfere in the Americas. This was a defining moment in the foreign policy of the United States. The Monroe Doctrine was adopted in response to American and British fears over Russian and French expansion into the Western Hemisphere.[56]

Indian removal[edit]

Settlers crossing the Plains of Nebraska.

In 1830, Congress passed the Indian Removal Act, which authorized the president to negotiate treaties that exchanged Native American tribal lands in the eastern states for lands west of the Mississippi River.[57] Its goal was primarily to remove Native Americans, including the Five Civilized Tribes, from the American Southeast; they occupied land that settlers wanted. Jacksonian Democrats demanded the forcible removal of native populations who refused to acknowledge state laws to reservations in the West; Whigs and religious leaders opposed the move as inhumane. Thousands of deaths resulted from the relocations, as seen in the Cherokee Trail of Tears.[58] Many of the Seminole Indians in Florida refused to move west; they fought the Army for years in the Seminole Wars.

Second Great Awakening[edit]

Main article: Second Great Awakening

The Second Great Awakening was a Protestant revival movement that affected the entire nation during the early 19th century and led to rapid church growth. The movement began around 1790, gained momentum by 1800, and, after 1820 membership rose rapidly among Baptist and Methodist congregations, whose preachers led the movement. It was past its peak by the 1840s.[59]

It enrolled millions of new members in existing evangelical denominations and led to the formation of new denominations. Many converts believed that the Awakening heralded a new millennial age. The Second Great Awakening stimulated the establishment of many reform movements—including abolitionism and temperance designed to remove the evils of society before the anticipated Second Coming of Jesus Christ.[60]

Abolitionism[edit]

After 1840 the growing abolitionist movement redefined itself as a crusade against the sin of slave ownership. It mobilized support (especially among religious women in the Northeast affected by the Second Great Awakening). William Lloyd Garrison published the most influential of the many anti-slavery newspapers, The Liberator, while Frederick Douglass, an ex-slave, began writing for that newspaper around 1840 and started his own abolitionist newspaper North Star in 1847.[61] The great majority of anti-slavery activists, such as Abraham Lincoln, rejected Garrison's theology and held that slavery was an unfortunate social evil, not a sin.[62][63]

Westward expansion and Manifest Destiny[edit]

Main article: American frontier

The American colonies and the new nation grew very rapidly in population and area, as pioneers pushed the frontier of settlement west.[64] The process finally ended around 1890-1910 as the last major farmlands and ranch lands were settled. Native American tribes in some places resisted militarily, but they were overwhelmed by settlers and the army and after 1830 were relocated to reservations in the west. The highly influential "Frontier Thesis" argues that the frontier shaped the national character, with its boldness, violence, innovation, individualism, and democracy.[65]

Recent historians have emphasized the multicultural nature of the frontier. Enormous popular attention in the media focuses on the "Wild West" of the second half of the 19th century. As defined by Hine and Faragher, "frontier history tells the story of the creation and defense of communities, the use of the land, the development of markets, and the formation of states". They explain, "It is a tale of conquest, but also one of survival, persistence, and the merging of peoples and cultures that gave birth and continuing life to America."[65]

Through wars and treaties, establishment of law and order, building farms, ranches, and towns, marking trails and digging mines, and pulling in great migrations of foreigners, the United States expanded from coast to coast fulfilling the dreams of Manifest Destiny. As the American frontier passed into history, the myths of the west in fiction and film took firm hold in the imagination of Americans and foreigners alike. America is exceptional in choosing its iconic self-image. "No other nation," says David Murdoch, "has taken a time and place from its past and produced a construct of the imagination equal to America’s creation of the West."[66]

From the early 1830s to 1869, the Oregon Trail and its many offshoots were used by over 300,000 settlers. '49ers (in the California Gold Rush), ranchers, farmers, and entrepreneurs and their families headed to California, Oregon, and other points in the far west. Wagon-trains took five or six months on foot; after 1869, the trip took 6 days by rail.[67]

American occupation of Mexico City during the Mexican-American War.

Manifest Destiny was the belief that American settlers were destined to expand across the continent. This concept was born out of "A sense of mission to redeem the Old World by high example... generated by the potentialities of a new earth for building a new heaven."[68] Manifest Destiny was rejected by modernizers, especially the Whigs like Henry Clay and Abraham Lincoln who wanted to build cities and factories—not more farms.[69] However Democrats strongly favored expansion, and they won the key election of 1844. After a bitter debate in Congress the Republic of Texas was annexedin 1845, which Mexico had warned meant war. War broke out in 1846, with the homefront polarized as Whigs opposed and Democrats supported the war. The U.S. army, using regulars and large numbers of volunteers, easily won the Mexican-American War (1846–48). The 1848 Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo made peace; Mexico recognized the annexation of Texas and ceded its claims in the Southwest (especially California and New Mexico). The Hispanic residents were given full citizenship and theMexican Indians became American Indians. Simultaneously gold was discovered, pulling over 100,000 men to northern California in a matter of months in the California Gold Rush. Not only did the then president James K. Polk expand America's boarder to a fraction of Mexico but he also annexed the north western frontier known as the Oregon Territory.[70]

Divisions between North and South[edit]

Main articles: Origins of the American Civil War and American Civil War

The central issue after 1848 was the expansion of slavery, pitting the anti-slavery elements that were a majority in the North, against the pro-slavery elements that overwhelmingly dominated the white South. A small number of very active Northerners were abolitionists who declared that ownership of slaves was a sin (in terms of Protestant theology) and demanded its immediate abolition. Much larger numbers were against the expansion of slavery, seeking to put it on the path to extinction so that America would be committed to free land (as in low-cost farms owned and cultivated by a family), free labor (no slaves), and free speech (as opposed to censorship rampant in the South). Southern whites insisted that slavery was of economic social and cultural benefit to all whites (and even to the slaves themselves), and denounced all antislavery spokesmen as "abolitionists."[71]

Religious activists split on slavery, with the Methodists and Baptists dividing into northern and southern denominations. In the North, the Methodists, Congregationalists and Quakers included many abolitionists, especially among women activists. The Catholic, Episcopal and Lutheran denominations largely ignored the slavery issue.[72]

The issue of slavery in the new territories was seemingly settled by the Compromise of 1850 brokered by Whig Henry Clay and Democrat Stephen Douglas; the Compromise included admission of California as a free state. The sore point was the Fugitive Slave Act, which increased federal enforcement and required even free states to cooperate in turning over fugitive slaves to masters. Abolitionists fastened on the Act to attack slavery, as in the best-selling anti-slavery novel Uncle Tom's Cabin by Harriet Beecher Stowe.[73]

The Compromise of 1820 was repealed in 1854 with the Kansas-Nebraska Act, promoted by Senator Douglas in the name of "popular sovereignty" and democracy. It permitted settlers to decide on slavery in each territory, and allowed Douglas to say he was neutral on the slavery issue. Antislavery forces rose in anger and alarm, forming the new Republican Party. Pro and anti-forces rushed to Kansas to vote slavery up or down, resulting in a mini civil war called Bleeding Kansas. By the late 1850s the young Republican Party dominated nearly all northern states and thus the electoral college, and insisted that slavery would never be allowed to expand (and thus would slowly die out).[74]

T88110-4.

- Jump up^ A. Grove Day, Coronado's Quest: The Discovery of the Southwestern States (1940) online

- Jump up^ David J. Weber, New Spain's Far Northern Frontier: Essays on Spain in the American West, 1540–1821 (1979)

- Jump up^ Jaap Jacobs, The Colony of New Netherland: A Dutch Settlement in Seventeenth-Century America (2nd ed. Cornell University Press; 2009) online

- Jump up^ Brebner, John Bartlet. New England's Outpost : Acadia before the Conquest of Canada. Archon Books Hamden, Conn. 1927

- Jump up^ Dean Jobb, The Cajuns: A People's Story of Exile and Triumph (2005)

- Jump up^ Allan Greer, "National, Transnational, and Hypernational Historiographies: New France Meets Early American History,"Canadian Historical Review (2010) 91#4 pp 695–724

- Jump up^ Mintz, Steven. "Death in Early America". Digital History. Retrieved February 15, 2011.

- Jump up^ Henretta, James A. (2007). "History of Colonial America".Encarta Online Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on October 31, 2009.

- Jump up^ Barker, Deanna. "Indentured Servitude in Colonial America". National Association for Interpretation, Cultural Interpretation and Living History Section. Archived from the original on October 24, 2009.

- Jump up^ James Davie Butler, "British Convicts Shipped to American Colonies," American Historical Review (1896) 2#1 pp. 12-33 in JSTOR

- Jump up^ Tougias, Michael (1997). "King Philip's War in New England". HistoryPlace.com.

- Jump up^ Oatis, S^ ^ "Composition of Congress by Party 1855–2013 —". Infoplease.com. Retrieved September 17, 2012.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)